I have written and spoken about this many times before, yet it is necessary once again to emphasize that when I write about a visual exhibition, I am not writing about a person or a gallery; I am writing about a world that has awakened that experience and confrontation within me. Consequently, every book, every film, every sculpture awakens a part of the emotions in us that were previously dormant or half-dormant. The duration of this emotional awakening in you is deeply connected to the depth that the artist, writer, or philosopher has stirred in their work and naturally in the audience.

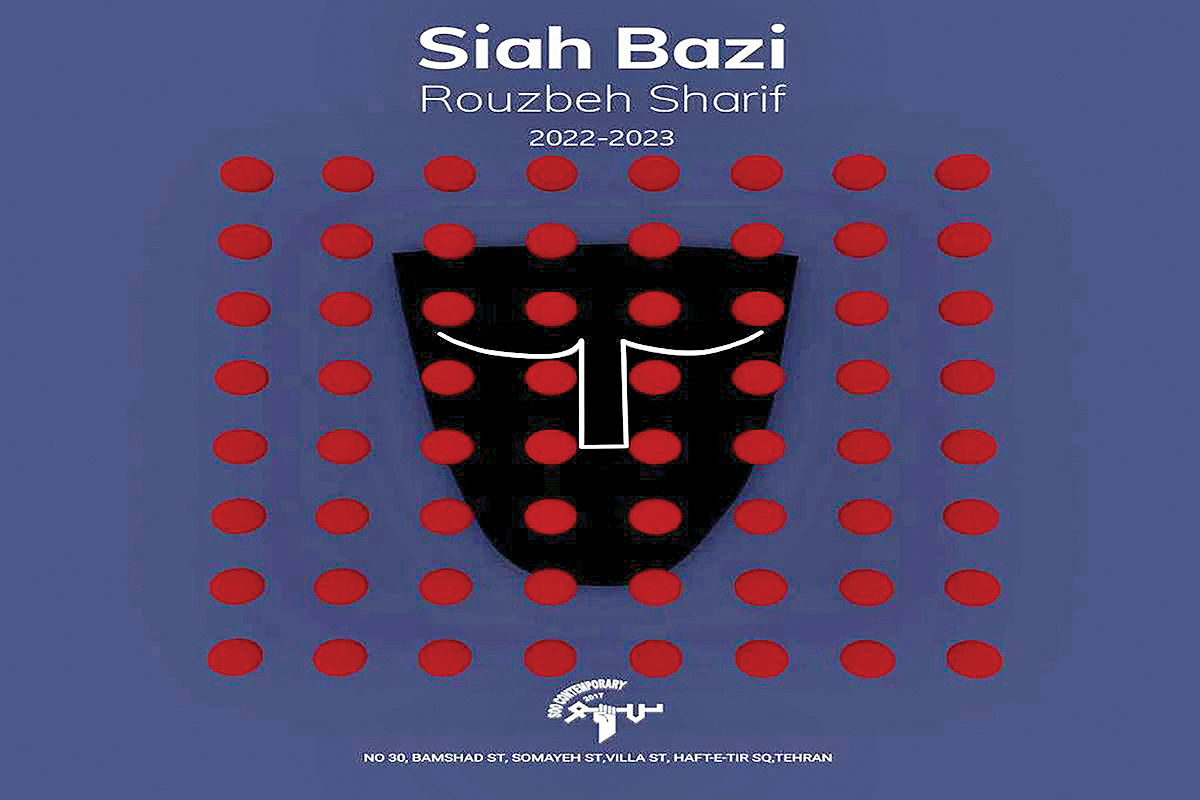

Moreover, the moment of observation also plays a significant role in the reception of literary and artistic works. The Siah Bazi exhibition at Soo Gallery has been placed before the audience after a relatively long hiatus in the activities of Iranian galleries, during a time when avoiding political inferences is almost impossible and difficult when compared to any cultural creation. Therefore, I postpone my interpretations of the meaning of the works to another time and focus on the event itself in general terms.

The First Act

During my childhood, I had gone to puppet theatre several times; its colourful and musical world, besides the joy of children, created an atmosphere where there were no jeeps of law enforcement patrolling the streets, no military marches, sirens warning of Sadam’s bombs. People were kind and cheerful, and there was no sign of the angry society of that time in the theatre hall. Back then, employees were given annual cultural coupons for theatre, cinema, and circus, which either meant spending evenings at mainstream theatres and cinemas or taking children to a few children’s theatre venues.

Fortunately, my parents used our small family’s allotment from the Revolutionary Government for attending events at the Children’s Intellectual Development Centre halls. The entrance to the Laleh Park hall was like a gateway to paradise for me; the puppets were part of a parallel world where the tales of faery kings were prominent, and sounds, colors, and chairs came alive to entertain children. The characters from these theater performances came with me to school every day; they were my childhood saviours trapped in the ideological conflicts of adults.

Years passed until I discovered that one of the important puppet makers of the sixties was a sculpture teacher at the art college. I attended his class, and our acquaintance began. When Bijan Nemati Sharif talked about his art, I understood that, like me with puppets, he had escaped from the bitter reality of the world through art.

Now, in these past few years, his son Roozbeh has followed in his father’s footsteps. It is likely that Roozbeh’s work continues in the same emotional vein as his father’s, so I am not indifferent to his exhibition at Soo Gallery. In this sense, I cannot overlook Bijan’s presence in his son, which is probably my fault, as I cannot acknowledge Bahman Kiarostami’s cinema without Abbas Khan.

The Second Act

When David Donald speaks of the incongruity of historical matters with present times, he effectively reshapes the functional relationship between form, content, and their connection to time in a different way; many past forms have lost the ability to converse in the language of the present. Similarly, when Arthur Danto published his End of Art article in 1984, he discussed the lack of connection between norms in two temporal situations. This discrepancy becomes more prominent when it comes to artists who are known as having famous artists for parents; with this argument, I initially hesitated to write about Roozbeh Nemati Sharif because I believe he has followed in his father’s footsteps, which for me is not very commendable.

But more importantly, this brings me back to my personal understanding of Bijan. He was a talented and innovative artist who did not have the opportunity to mature in his work due to his premature death, and now his son has expanded this unfinished style with sincere and honorable dedication. However, this does not mean that I disregard Roozbeh’s seriousness in creating punk and funk spaces and adding them to Bijan’s taste.

With these additions, he has detoxified nostalgia from the previous style; that is, he does not lead the viewer to lament games in The Shahnameh and the common trivializations. This is also why the arena in his work plays more of a role than any color or smell. I believe that even if he had shown a bit more restraint in this exhibition at Soo Gallery, the result would have been better. In fact, the overcrowding of pieces in galleries has compelled one to see them superficially rather than contemplate deeply. Unfortunately, this longwindedness, which sometimes verges on frivolity, has detrimentally affected the emotional coherence of this arrangement.

The Third Act

The classical-modern spectator imagines that the catharsis of art resides exclusively in serious, absorbed, and solemn matters! Conversely, contemporary viewers consider the realm of art as playful and whimsical, to the extent that shortcomings, ironies, deficiencies, and bad acting in today’s art have overshadowed skillful seriousness. This epistemology reminds one of Bakhtin; by carnivalizing concepts, it discovers a force of independence that challenges somber culture and will ultimately bring it to its knees.

The presence of pop, kitsch; abstract zombies, exploration, punk mini-malls, and any form of exaggerated comedic gesture towards reality creates an ineffable language, as Julia Kristeva puts it, which will move towards deep social reintegration. Haji Firuz or the character Mubarak in puppet theater lives a life reminiscent of Bahlool’s folly and contemplation, which is as enlightening as it is compassionate and funny. A human figure with an innocent face blackened by coal that heralds the revolution of nature or the reform of their immoral, greedy master in the coldest days of the year or in the most sorrowful moments in history. This parody in the form and identity of Haji Firuz has kept us eager for him like this throughout the centuries as if he were the eternal guardian of truth.

Sharifi Namati’s father described a Shinto ritual where they do not throw away the worn-out puppet. Instead, they burn and turn it to ashes in a short lament in the temple so that its spirit can transform into another new puppet. Artists who have dedicated themselves to these humorous and sarcastic arts are mostly aware of this spiritual characteristic in objects and have accepted the principle that fleeting happiness will lead to profound sorrow. Even Epicurus could not account for this melancholic aspect of the soul in transient happiness. Perhaps many of us suffer from a form of cherophobia where, upon experiencing joy, we are immediately seized by torment. Of course, psychological therapies attribute this syndrome to childhood experiences resulting from the deprivation of happiness and prolonged suffering; a place where the joy of achievement is purified by the torment of sorrow. Roozbeh vividly reflects this characteristic in his sculptures and may well turn it into the central theme of his future works.

The Fourth Act

The final act, however, is about writing on an important and positive aspect of this exhibition, which is addressing the era of modular image production on platforms like Instagram, Twitter, TikTok, etc. In an age dominated by the narrative of socio-political discourse in the media over any other cognitive language, the production of visual signs, geoculture, and stereotypes comes into question. Roozbeh, contrary to the prevailing rhetoric, engages with the marginalized morphology and protests against the current state of Iranian plasticity. Simply put, he neither favors the marketable Orientalism nor does he draw from the signs of sentimental elitist art. Roozbeh has orchestrated a celebration akin to the colorful festival of Holi in India, with lavish expenditure and abundance of fluorescent colors, heralding the end of winter and the beginning of spring in the near future.